OBELISK

Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung,

Inv. Nr. 12800

More...

|

"Taken from among ruins, dust and sands,

An obelisk wandered to the foreign lands,

On exile like a banit, used to stand alone,

Offering no shadow with his heart of stone,

Standing silent, its spirit in the land of ghosts..."

(J. Słowacki, Letter to Aleksander H.)

|

Obelisk of Ramesses II came to the Poznań Archaeological Museum as a long-term

loan thanks to a personal initiative of professor Dietrich Wildung, the director

of the Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung in Berlin. Three-meters high granite

monolith bearing inscriptions of three rulers of the Nineteenth Dynasty is a

unique object. It is the only pharaonic obelisk in Poland and one of a few in

Europe. Poznań joined thus London, Paris, Rome, Florence, Munich and Istanbul,

cities that received other 'banits' from the land of pharaohs. Obelisk is not

only one of the most characteristic elements of ancient Egyptian culture, but

it belongs to the tradition of European art and architecture as well. Examples

of use of this motif as funerary or memorial monuments are innumerable. The

word 'obelisk' became in fact to mean a 'monument', 'memorial' even if its form

goes far from the ancient pattern. The roots of our culture reach really deep

- nothing can express this better than the obelisk standing in the middle of

St. Peter's square in Vatican. Ancient Egyptian solar symbol, piercing the sky

with its pointed top, sets the axis of the world, joining earth and sky, humanity

and divine realm, affinity and afterlife. Life-giving sunrays, uttered in stone,

symbolize what were the most optimistic features of the Egyptian religion: light,

affirmation of life, power of positive magic. The ancient Egyptians believed

that not only people and gods, but also some buildings and objects have their

'souls' called ba. Obelisk of Ramesses II hosted in Poznań thanks to German-Polish

friendship is therefore a LIVING proof of a relativity of borders - not only

the political ones - and unity of the world.

The obelisk is made of grey granite (granodiorite), quarried at Aswan.

Its base length is 53 cm, which corresponds to one Egyptian cubit. Its height,

probably intended to be exactly six cubits, is now reduced to 300 cm because

of damage of the pyramidion. An estimated weight of the obelisk is approx. 1800

kg.

The obelisk came from the city of Hut-heri-ib (Greek Athribis, present Tell Atrib,

a district of town Benha) in the Nile Delta, the capital of the 10th nome (province)

of Lower Egypt. In the antiquity it was standing in front of the temple of god

Khenti-kheti, together with another obelisk kept now in the Egyptian Museum in

Cairo. Removed from Athribis, it was used as a threshold in a house in Cairo

in the 19th century (damaged inscriptions on one of the sides and a destroyed

pyramidion are traces of this re-use). After its discovery therein it was bought

in 1895 by C. Reinhardt. Brought to Europe, since 1896 it has been in the possession

of the Berlin museum.

The four sides of the obelisk bear incised hieroglyphic inscriptions with names

and titles of three pharaohs of the Nineteenth Dynasty: Ramesses II (1279-1213

BC), Merenptah (1213-1203 BC) and Sethi II (1200-1194 BC). The texts are similarly

distributed on all of the sides, they differ, however, in details, giving different

names and epithets of the kings, and names of the gods worshipped at Athribis.

Ramesses II's text (the middle column) has been cut in a visible depression,

indicating that an earlier inscription may have existed, removed before the decoration

of the obelisk by this king. It is therefore probable that Ramesses usurped an

obelisk erected at Athribis by an earlier ruler, who might have been Amenhotep

III. Merenptah, son and successor of Ramesses II, added his names at the bottom

of the obelisk on both sides of his father's text. Upper parts of both lateral

columns were subsequently filled in with the titulary of Sethi II. Signs representing

god Seth in the king's name were destroyed in later times. The reason for this

was an increasing hostility against this god, who was considered in the Late

Period not only an enemy of Osiris, but also the patron of foreign nations invading

Egypt.

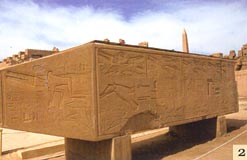

The bases of both Athribis obelisks, now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, are

made of quartzite and decorated with representations of Ramesses II making offerings

to local deities and two solar gods Horakhty and Atum.

NEW PYRAMIDION

At some point in the history (Middle Ages?) the obelisk was transferred from

Athribis to Cairo and re-used as a threshold in a house. At that time probably

the original pyramidion was cut away. Whether it was once covered with a metal

sheet or not cannot be determined. Anyway, it came to Poznań in this state of

preservation, with a plywood pyramidion, painted grey, placed on its top. The

director of Poznań Archaeological Museum, the late professor Lech Krzyżaniak

decided then that a new, gilded pyramidion would be made as a sign of gratefulness

for the Berlin museum. The idea was to show how it may have looked in the antiquity.

This project was realized in October 2003 and since then the pyramidion is placed

on the top of the obelisk.

The assumption was that the proportions should be less or more like other Eighteenth

Dynasty obelisks and it appeared that the height of it could be exactly one cubit

(52.5 cm), which agrees with the observation that the shaft of the obelisk was

probably planned to be 6 cubits high. The new pyramidion has thus the dimensions

of 36 x 37 cm (the base, not exactly square, which reflects the damaged surface

of the top of the obelisk), and its vertical height is 52.5 cm, which makes about

55 cm along the walls. It was made of 2 mm steel plate, painted with anti-corrosion

paint, covered with mixtion, and finally, covered with leaves of 23-carat gold.

Of course it is not attached to stone, as one could imagine the ancient ones

were. It is fixed upon a low base, which is a cast of the preserved surface of

the top of the obelisk, made of special cement-like material.

There is only one other obelisk in the world that got such a gilded pyramidion

(for obvious reasons no original ones are preserved from the antiquity). It is

the obelisk of Ramesses II that stood once in front of the Luxor temple, and

now in the Place de la Concorde in Paris. In 1997 its pyramidion was covered

with a bronze plate, gilded with 23.5 carat gold (as a remark of Franco-Egyptian

friendship, on the occasion of the Egyptian president Mubarak's visit to France).

The cost was 250 000 $. The Poznań pyramidion was a bit cheaper.

OBELISKS

OBELISKS

fig. 1

Term

The name obelisk, denoting in European languages the Egyptian and egyptianizing

monuments, derives from Greek οβελισκοç

(obeliskos),

'small spit'. This name was given to Egyptian monoliths by Greek mercenaries

who served the pharaohs in the 6th cent. BC. It reflected the fascination of

the unusual shape of obelisks, referred to also in the Arabic word ﺔﺂﺳﻤ misalla,

'a large packing needle'. The Ancient Egyptian term for an obelisk was

techen.

The etymology of the word is not clear, but it can possibly be related to another

word thus pronounced, meaning 'a door-leaf'. Since obelisks were set in pairs,

the ancient Egyptian texts usually refer to tekhenui, 'the two obelisks'. Hatshepsut,

a female pharaoh, ruling in 1473-1458 BC, proudly spoke in her inscription in

the Karnak temple (fig.1): 'The king (i.e. Hatshepsut)

himself erected two large obelisks for her father Amun-Ra in front of the main

columned hall, covered with electrum in great quantity. Their heads pierce the

sky and light up the two lands like the sun-disk. Nothing has been done like

that since primeval times'.

techen.

The etymology of the word is not clear, but it can possibly be related to another

word thus pronounced, meaning 'a door-leaf'. Since obelisks were set in pairs,

the ancient Egyptian texts usually refer to tekhenui, 'the two obelisks'. Hatshepsut,

a female pharaoh, ruling in 1473-1458 BC, proudly spoke in her inscription in

the Karnak temple (fig.1): 'The king (i.e. Hatshepsut)

himself erected two large obelisks for her father Amun-Ra in front of the main

columned hall, covered with electrum in great quantity. Their heads pierce the

sky and light up the two lands like the sun-disk. Nothing has been done like

that since primeval times'.

Form

and material

Form

and material

Obelisk is a huge stone pillar with a square base, tapering towards the top,

which is pyramid-shaped (hence the top of an obelisk is called a pyramidion).

Ancient Egyptian obelisks were monolithic, i.e. made of a single block of stone.

They were usually made of granite, but the quartzite, limestone and greywacke

examples are known as well. On the side were engraved hieroglyphic inscriptions

giving the royal titulary (names and epithets)

of a pharaoh, and dedicatory texts for gods. The pyramidia were often decorated

with representations of solar symbols (e.g. winged scarabei), or the king protected

by a god (fig.2). The solar connotations of the obelisks

were additionally stressed by a peculiar form of their decoration: pyramidia

or even the upper parts of the shafts might have been covered with golden, electrum

(an alloy of gold and silver), or copper sheets that gleamed reflecting the

sunrays.

Making, transporting and erecting

The 'production technology' of great obelisks made of hard stones has been reconstructed

fairly well, basing on evidence of texts, traces on preserved monuments, discovered

tools, and especially by examination of unfinished obelisks still lying in

the Aswan quarries. The rock was crushed with basalt hammers and a trench was

cut around a planned monolith. The stone was then partially cut underneath.

Next, it was levered with wooden beams and separated from the floor. It was

not before the Graeco-Roman times that another system was employed, namely

cutting narrow holes in which metal wedges were hit, and a stone broken along

the line of holes. The example of the obelisk of Sethi I preserved in the Gebel

Gulab quarry suggests that (at least sometimes) obelisks were decorated already

in the quarry, and the inscriptions could have been engraved on the accessible

sides of the stone before the final cut of the base. Obelisks were transported

to their final destination site (e.g. from Aswan to Thebes) by water, on specially

constructed cargo barks towed by a group of ships. Such a fleet is represented

in the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari (fig.3).

Between the quarry and the harbour, and after the reloading at the destination

place, the obelisks were moved on sledges, towed by gangs of workers on specially

built roads (fig.4). They were placed in front of

pylons (towered temple entrances) by moving along ramps of small inclination,

or by gradual levering of one end of the stone. When the obelisk base fit grooves

in the pedestal, it was erected to vertical position by means of ropes (fig.5).

Symbolic meaning

Obelisks were considered as sacred to the sun god, representing the sunrays embodied

in stone. They marked a symbolic axis of the world, being a cosmic pivot point

and gate between earth and sky. Dedicated by the kings, they emphasized the

role of the pharaoh as an intermediary between humanity and the gods, especially

the sun god Ra. In this function they were erected before the entrances to

the temples, usually set in pairs symmetrically on both sides of the gate axis.

Tops of obelisks, covered with golden sheets, gleamed in the rays of the sun,

symbolizing the life-giving power of Ra. During the Old Kingdom obelisks were

erected in pairs flanking the entrance to a tomb, or before a false-door -

a magical gateway between the realm of the dead and the

world of living (fig. 6), (fig.

7).

It reflected the fact that obelisks were likewise images of benben (mythical

primeval hill, i.e. the first land that emerged from a primeval ocean when the

world was created and the creator god, Atum, appeared on it). Benben-stone in

the temple at Heliopolis (possibly a meteorite of peculiar shape) was a memorial

of that event. Also pyramids and obelisks symbolized the primeval hill and their

tops (pyramidia) were therefore called benbenet. The dead, reborn to

a new life, not only repeated in some way his or her own birth, but also identified

himself with the creator god, joining the sun in its eternal cycle of rising

and setting.

|

|

HISTORY

Antiquity

'The one who fills Heliopolis with obelisks that their rays may illuminate the

temple of Ra'

'Making monuments as innumerable as the stars of heaven. His works join the sky.

When Ra shines, he rejoices because of the obelisks in his temple of millions

of years.'

(inscriptions of Sethi I and Ramesses II on the obelisk of Piazza

del Popolo in Rome) |

The

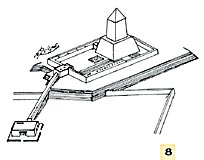

oldest known obelisk, or rather 'obeliskoid', was an enormous building

constituting a central structure in the sun-temple of Niuserra (Fifth

Dynasty, ca. 2400 BC) at Abusir. It was a huge obelisk standing on

a tall, trapezoidal base (fig.8).

The whole structure was built of limestone blocks and cased with granite.

It reached the height of 57 metres. The earliest 'classical' obelisks

were erected in the temple of Heliopolis by the Sixth Dynasty rulers

Teti and Pepi II, and subsequently many later kings added there their

own monuments. Today at the site of Ancient Heliopolis

(present-day el-Matariya, a district of Cairo) is standing a granite obelisk

of Senwosret I (Twelfth Dynasty, ca. 1950 BC). During the Middle and New Kingdoms

it became common to place obelisks in front of temple entrances. They were dedicated

to state gods, especially the solar deities as Ra-Horakhty or Amon-Ra. The occasion

for erection of obelisks were often the royal jubilee or triumph over enemies.

The New Kingdom obelisks

The

oldest known obelisk, or rather 'obeliskoid', was an enormous building

constituting a central structure in the sun-temple of Niuserra (Fifth

Dynasty, ca. 2400 BC) at Abusir. It was a huge obelisk standing on

a tall, trapezoidal base (fig.8).

The whole structure was built of limestone blocks and cased with granite.

It reached the height of 57 metres. The earliest 'classical' obelisks

were erected in the temple of Heliopolis by the Sixth Dynasty rulers

Teti and Pepi II, and subsequently many later kings added there their

own monuments. Today at the site of Ancient Heliopolis

(present-day el-Matariya, a district of Cairo) is standing a granite obelisk

of Senwosret I (Twelfth Dynasty, ca. 1950 BC). During the Middle and New Kingdoms

it became common to place obelisks in front of temple entrances. They were dedicated

to state gods, especially the solar deities as Ra-Horakhty or Amon-Ra. The occasion

for erection of obelisks were often the royal jubilee or triumph over enemies.

The New Kingdom obelisks  attained

large dimensions. The obelisk of Thotmes III at Lateran in Rome is over 32 m

high and possibly weights about 455 tons. The largest of known obelisks, still

lying in a quarry at Aswan, is 41.75 m long, and its estimated weight is 1168

tons (fig.9). It is

possibly to be dated to the Eighteenth Dynasty. It was abandoned when the stone

has started to crush, which made its extraction impossible, even after a planned

reduction of dimensions. From among numerous obelisks rising once in Egypt only

a few has been preserved. These are the monoliths of Ramesses II at Luxor (fig. 10),

(fig. 11),

Thotmes I and Hatshepsut at Karnak, and the obelisks of Ramesses II from Tanis

(re-erected in Cairo). Many pharaonic obelisks were taken from Egypt abroad.

It started already in ancient times. Octavian August brought in 10 BC two obelisks

to Rome, and had them erected at the Circus Maximus and Campus Martius. Roman

emperors not only usurped the obelisks of former rulers of Egypt, but also ordered

new ones to be made and erected for their own glory at public places. It is

Rome that is the site of the highest number of standing obelisks (thirteen).

Already in ancient times also another obelisk was transferred to Constantinople

(present-day Istanbul), where it was placed on the hippodrome.

attained

large dimensions. The obelisk of Thotmes III at Lateran in Rome is over 32 m

high and possibly weights about 455 tons. The largest of known obelisks, still

lying in a quarry at Aswan, is 41.75 m long, and its estimated weight is 1168

tons (fig.9). It is

possibly to be dated to the Eighteenth Dynasty. It was abandoned when the stone

has started to crush, which made its extraction impossible, even after a planned

reduction of dimensions. From among numerous obelisks rising once in Egypt only

a few has been preserved. These are the monoliths of Ramesses II at Luxor (fig. 10),

(fig. 11),

Thotmes I and Hatshepsut at Karnak, and the obelisks of Ramesses II from Tanis

(re-erected in Cairo). Many pharaonic obelisks were taken from Egypt abroad.

It started already in ancient times. Octavian August brought in 10 BC two obelisks

to Rome, and had them erected at the Circus Maximus and Campus Martius. Roman

emperors not only usurped the obelisks of former rulers of Egypt, but also ordered

new ones to be made and erected for their own glory at public places. It is

Rome that is the site of the highest number of standing obelisks (thirteen).

Already in ancient times also another obelisk was transferred to Constantinople

(present-day Istanbul), where it was placed on the hippodrome.

|

|

Modern times

'Good bye! If you go to Thebes, do send me a little

obelisk'

(Josephine to Napoleon leaving for Egypt) |

During the Renaissance, obelisks discovered among the ruins of Rome

once more gained attention. In 1586 Domenico Fontana with help of 1000

people and 100 horses placed one of them in St. Peter's Square in Vatican.

This monument (fig.12), 25 metres high,

was once erected in Alexandria by order of August, and then brought

to Rome by Caligula. On popes' initiative many obelisks were set in

the squares of Rome, usually topped with Christian symbols. Discoveries

made during Napoleon's expedition to Egypt (1798-99) and decoding of

the hieroglyphs by J.-F. Champollion in 1822 enabled the development

of scientific Egyptology, and started the vogue for ancient Egypt.

Nineteenth century Egyptomania

could not omit such admirable markers of the past as obelisks. The

rulers of Egypt of that time offered the monoliths found in Alexandria

(so-called needles of Cleopatra, fig.13)

to the Great Britain and the United States, and one of the two standing

before the Luxor temple was given to France. The obelisks were successively

moved to Paris (in 1831-33), London (1877-78) and New York (188-81).

Numerous contemporary imitations of ancient monuments include the obelisk

in Washington D.C., which is 168 m high, although not monolithic, but

constructed of blocks.

1000

people and 100 horses placed one of them in St. Peter's Square in Vatican.

This monument (fig.12), 25 metres high,

was once erected in Alexandria by order of August, and then brought

to Rome by Caligula. On popes' initiative many obelisks were set in

the squares of Rome, usually topped with Christian symbols. Discoveries

made during Napoleon's expedition to Egypt (1798-99) and decoding of

the hieroglyphs by J.-F. Champollion in 1822 enabled the development

of scientific Egyptology, and started the vogue for ancient Egypt.

Nineteenth century Egyptomania

could not omit such admirable markers of the past as obelisks. The

rulers of Egypt of that time offered the monoliths found in Alexandria

(so-called needles of Cleopatra, fig.13)

to the Great Britain and the United States, and one of the two standing

before the Luxor temple was given to France. The obelisks were successively

moved to Paris (in 1831-33), London (1877-78) and New York (188-81).

Numerous contemporary imitations of ancient monuments include the obelisk

in Washington D.C., which is 168 m high, although not monolithic, but

constructed of blocks.

When the Egyptian government realised that the capital of Egypt does not possess

any standing obelisk, two monuments of Ramesses II were moved from Tanis in

the Delta and erected in Cairo (at Zamalek island and at the airport). The youngest

standing object of this kind in Egypt is an obelisk set in the middle of the

courtyard in the memorial monument of the German soldiers at El-Alamein, the

site of the famous battle during the World War II (fig.14).

An analogous role is played by one of the many Poznań monuments - an enormous

obelisk in the Citadel, a memorial of the Soviet soldiers from 1945 (fig.15).